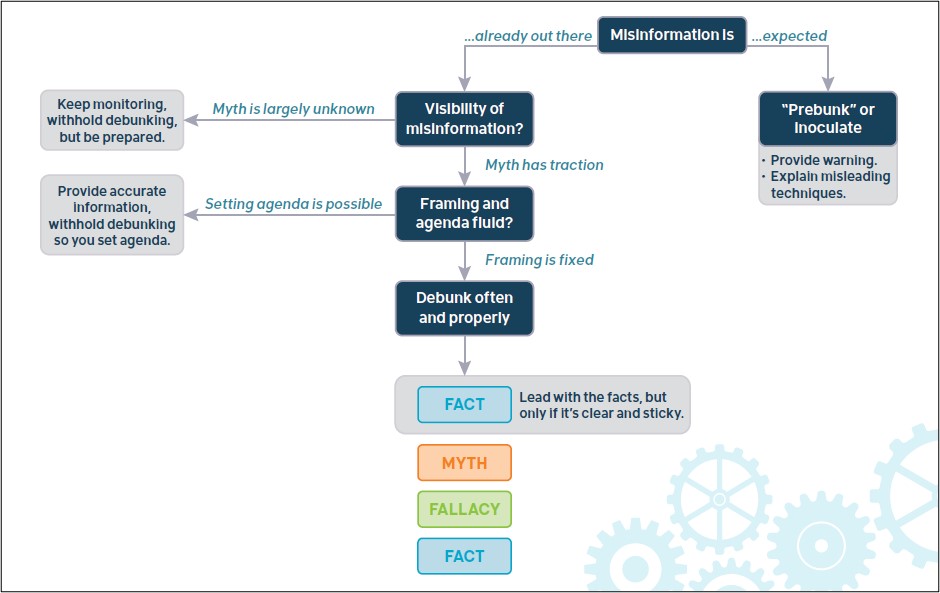

(Header image: from Lewandowsky et al. 2012:122)

I was recently invited to give a guest lecture to students in an Abuses of Antiquity course at a local (to me) university, in which one of their topics is pseudoarchaeology. One of the things I was asked to talk about is, well, talking. To be more specific, to talk about communication methods for archaeologists who may be engaging with pseudoarchaeology, in a myriad of ways and a myriad of spaces. Online spaces is usually the first thing that comes to my mind, things like social media, YouTube videos, TikTok, podcasts, etc. My presentation largely revolves around a couple of things I’ve written/am writing, in which I’ve briefly touched on communication methods. One of those things was published in Archaeological Prospection, which you can read here. The other is a book chapter I’m just wrapping up edits on, and will link to here once the book is published.

I’m one of those critical archaeologists who is always thinking about how “archaeological interpretations presented to the public may acquire a meaning unintended by the archaeologist and not to be found in the data” (Mark Leone et al. 1987:284). And part of that includes thinking not just about how someone’s own ideologies and worldviews may shape the ways they interpret knowledge about the past, which can range from an innocent misinterpretation of archaeological information to a more harmful disinformative manipulation of that information, but also thinking about how that the ways we communicate archaeological knowledge also influences the way people interpret knowledge about the past. How we say something is just as important as what we’re saying. That can be said for presenting our initial archaeological knowledge, but it can also be said for how we react to or engage with misinterpretations when they occur.

Much attention has been placed on engaging with pseudoarchaeological interpretations of the past, and I will say that I’m writing this post with that in mind. When engaging with pseudoarchaeology, archaeologists have long turned to debunking (exposing the falseness of something). Debunking is definitely an approach we can use (and keep reading for advice on effective debunking methods), but it’s not the only approach and we should not solely focus on debunking. The problem with debunking is that its success is variable and there is risk for backfire (it’s not common but it does happen). It’s better to be proactive than reactive, to prevent than to cure, and so pre-bunking is another important approach to consider. What I’d like to do in the rest of this post is to share links and brief explainers to some of my favourite resources for considering communication methods, such as debunking and pre-bunking. These were not written by archaeologists, they come from mis/disinformation experts outside of archaeology. But when we combine these frameworks with our archaeological knowledge and expertise then we as archaeologists become very well-suited for tackling mis/disinformation in our own discipline (hooray for multi-disciplinary approaches!). It takes time and effort and dedication to learning and putting the frameworks into practice, but I sincerely believe that it is worth that time, effort, and dedication. These are resource I’ve learned a lot from and that I’m actively working on incorporating into my own work, and so I hope they will also be useful for others who are seeking ways to make their communications stronger, whether as a collective or as individuals! So follow along for a brief annotated bibliography:

Recognizing conspiratorial thinking – To begin with, it helps to be able to recognize conspiratorial thinking and differentiate between conspiracies and conspiracy theories. The Conspiracy Theory Handbook is a handy, brief guide that breaks down the CONSPIR characteristics of conspiracy theories.

The Oxygen of Amplification – I will always recommend the Oxygen of Amplification. It was written for journalists, but is really applicable to more than just journalists. This is a worthwhile document for learning to recognize bad faith strategies for spreading hate and harm and how we can be taken advantage of for those purposes (e.g. antagonizing us into responding in ways that spread their messages). The document also offers better practices for discussing false information, bad faith strategies, bad faith actors, etc. in ways that minimizes their amplification and helps us identify when we may be unintentionally doing the work for them.

Relatedly, I also found “Disinformation and Echo Chambers: How Disinformation Circulates on Social Media Through Identity-Driven Controversies” by Carlos Diaz Ruiz et al. (2023) to be really insightful. Diaz Ruiz et al. break down rhetorical strategies for spreading disinformation on social media, namely through “identity-based grievances” and “seeding and echoing” phases in social media arguments, in which they found that “as grudges intensify, back-and-forth argumentation becomes a form of knowing that solidifies viewpoints” and “resists fact-checking.” Ultimately what this paper and the Oxygen of Amplification teaches us is that, to put it bluntly, sometimes we can unintentionally make a situation worse. Which is something we definitely don’t want to do. Being able to identify those situations is a really useful way we can find more effective ways to interact with them.

Pre-Bunking – Archaeologists have long turned to debunking (exposing the falseness of something) as a strategy for engaging with pseudoarchaeology or other forms of mis/disinformation. Debunking is important, but debunking’s efficacy is variable, dependent on a range of conditions including how we debunk. There are some great guidelines for improving debunking, which I will share in the next section, but debunking should not be the only thing we do. Research has shown it is better to be proactive than reactive. To do that, we should turn more attention to pre-bunking. Pre-bunking (based on inoculation theory) is a way to offer a toolkit to people than enables them to recognize mis/disinformation and put up a personal shield against it. When you know what to look for, mis/disinformation loses its ability to deceive you. Pre-bunking should come first, if that is not an option then turn to debunking. You can provide pre-bunking information on a case-by-case basis, but technique-based pre-bunking is really valuable (and something I personally prefer to do) – exposing the general techniques that are used to deceive, essentially the red flags that you should look out for. Listed below are a few resources I find really useful for learning about pre-bunking:

Inoculation Theory and Misinformation – Jon Roozenbeek and Sander van der Linden (2021) (a brief overview of what pre-bunking is, what inoculation theory is, and suggestions on pre-bunking strategies, including technique-based pre-bunking)

Countering misinformation through psychological inoculation – Sander van der Linden (2023) (a much more detailed look at pre-bunking and inoculation theory)

Deconstructing climate misinformation to identify reasoning errors – John Cook et al. (2018) (this is a climate specific paper, but it has a really nice framework discussion)

Debunking – As I’ve already mentioned, pre-bunking should be first on the list. But sometimes it’s too late to pre-bunk, and that’s when debunking can be a good option. Why do I (and many others) think that debunking shouldn’t be a first choice? Because trying to reign back in mis/disinformation once it is out and has already spread is very difficult, for many reasons. One of which being the continued influence effect, in which retractions and debunking/fact-checking mis/disinformation does not always nullify its effects. Now, all that being said, there are ways to make debunking more effective (even to make retractions more effective), by following some great guidelines that were established by a lot of folks who have spent a lot of time studying de- and pre-bunking. There are two resources in particular that share really insightful information about debunking frameworks:

Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing – Stephan Lewandowsky et al. (2012) (provides a good discussion about the continued influence effect, good info on different types of backfire effects, and brief but numerous debunking strategies)

The Debunking Handbook 2020 – Stephan Lewandowsky et al. (2020) (an excellent handbook on its own, but especially in conjunction with the 2012 article I shared above, the handbook includes a clear and concise debunking framework that can be applied to any discipline, as well as great explainers behind each element of the framework)

*For an excellent example of a debunking video, I highly recommend “In Search of a Flat Earth” by Folding Ideas (Dan Olson)*

These are not the only resources I use in my work, but I reference these often because they provide really excellent overviews of complex problems. And, importantly, they offer practical solutions that aren’t discipline-specific. Meaning we can combine the offered solutions with our specialized knowledge as archaeologists to make these resources applicable to issues we see in archaeology. Patience and repetition are key, and we also have to be comfortable with failure because sometimes something won’t work out the way we hope it will. Overall, although I’ve shared these resources with mis/disinformation in mind, they’re really useful for just generally helping us strengthen our communication methods and I hope you find them as useful as I have!

One thought on “A [Semi-]Solicited Guide on Pre-bunking and Debunking”