Title image: The outside front cover (left) of the October 1928 Chalice Magazine, and the inside front cover (right) that was printed inside each issue from December 1927 onward, describing the symbolism of the outside cover design.

At the beginning of April I presented some of my PhD research on the conspiritual landscapes of Brother XII and the Aquarian Foundation at the 2025 BC Studies Conference, held at the University of British Columbia. The theme was “Place and Power,” and as such my presentation was focused on the concept of “places of power” and Brother XII’s conspiritual place-making. You can watch a video of my presentation (with captions) at the bottom of this post.

Beyond just discussing a bit of Aquarian Foundation history, my presentation demonstrated the ways that I, as a historical archaeologist, use archival materials within my research. Archives are, in a simple sense, described as “repositories in which public records or other primary historical records are stored” (Skowronek 2014:492). Stored within archives are archival materials, sometimes also called historical documents, archives, or records, which Peter Van Garderen (2007) defined as preserved information objects that record information that can be used as a memory aid or proxy for a past event. Archival materials can include written documents, visual recordings, and oral recordings and may be published or unpublished materials (Van Garderen 2007).

Archival materials are incredibly important for enabling me to examine how Brother XII and the Aquarian Foundation materially expressed their conspirituality within their landscapes, which includes land modifications, structures and other built features, and the material goods they produced and used. For this, I use archival materials to shine a light on the archaeology to give me more nuanced insight into that archaeology. My presentation doesn’t focus on the use of archival materials specifically, so I thought I would share a little bit here on how archival materials have two roles for me.

Documentary Archaeology and Archival Insights

With a focus on combining archival materials with archaeology, my research falls under the methodological theme of what Mary Beaudry referred to as documentary archaeology. Building from Beaudry’s introduction of documentary archaeology in 1988, Laurie Wilkie (2006:13) described documentary archaeology as “an approach to history that brings together diverse source materials related to cultures and societies that people the recent past,” which offers “understandings of the past not possible through single lines of evidentiary analysis.” Documentary archaeologists view “their ‘archive’ as including written records, oral traditions, and material culture – from both archaeological and curated sources” (Wilkie 2006:14), which compliment each other to enable historical archaeologists to uncover a fuller and more meaningful understanding of the past.

Wilkie (2006:16–20) described three primary goals documentary archaeologists have for using archival materials towards more insightful archaeological interpretations of the past. First, archaeologists may engage in archival research to identify the individuals and/or communities who lived at a site and how they may have organized that site. Second, archaeologists may use archival materials to gain further insight into the social-cultural context of the site’s occupation. And third, archaeologists may use archival materials to gain deeper understanding of the social meanings and lives of the material objects uncovered by archaeology. Different types of archival materials, for example census records versus diaries versus probate inventories, will reveal different information with regards to the three goals mentioned above, but all are useful in uncovering more nuanced understandings of archaeological sites.

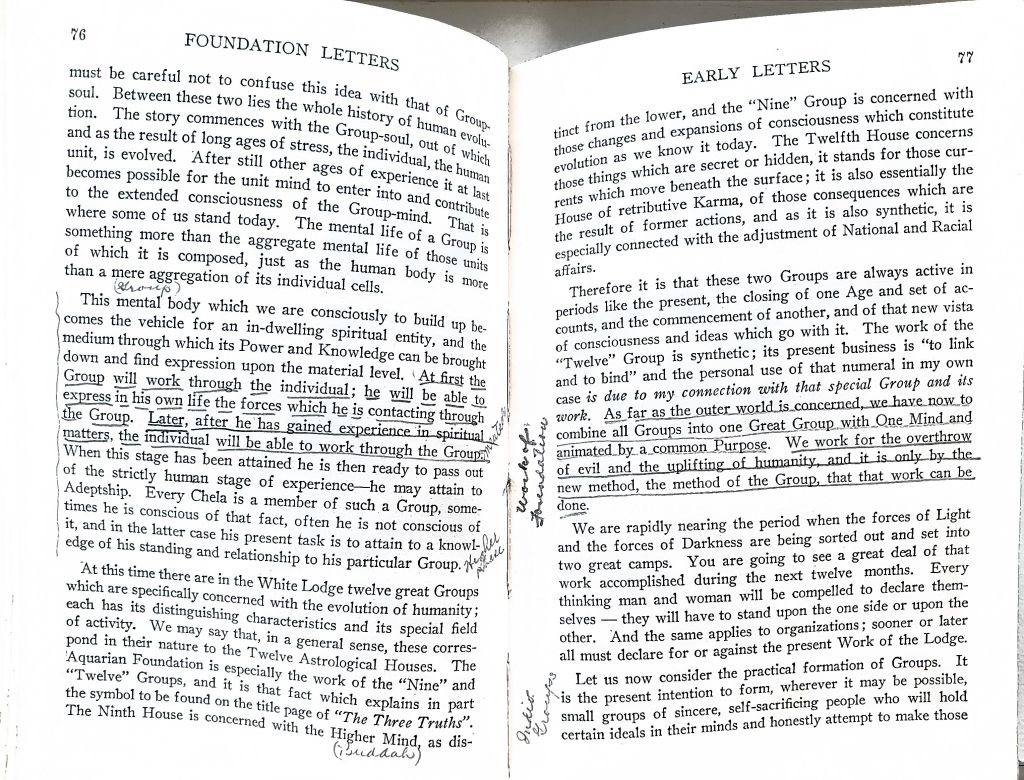

Brother XII and the Aquarian Foundation published a lot in their short period of activity (1926-1932), and their archival materials include books, pamphlets, and magazine articles (both published in external magazines and in their own short-lived magazine, The Chalice). All of these primary sources give me incredible insight into their conspiritual ideologies and all of the elements that went into forming their two core purposes as described by Brother XII: 1) To transition humanity into the 6th sub-race of the 5th Root Race and usher in the Age of Aquarius, and 2) to awaken humanity to the truth that a powerful cabal of of Jews and Catholics were conspiring to form a total world dictatorship. From an archaeological standpoint, these archival materials also provide crucial insight into the landscapes the Foundation built in British Columbia and how their ideologies were materially expressed in those landscapes through everything from land modifications, to built structures (including their social and spatial organization), to the material goods produced and used. Furthermore, specific archival materials may reveal information about specific landscapes. For example, the Foundation produced The Chalice magazine for one year from 1927 to 1928, during the time that they began building on Vancouver Island and Valdes Island, and as such The Chalice contains insight into those two specific landscapes. And Brother XII’s book, Unsigned Letters from an Elder Brother was published in 1930 and consists of letters written in 1929, during the time that the Foundation was building on DeCourcy Island. In addition to some commentary regarding Vancouver and Valdes islands, Unsigned Letters also contains insight specific to DeCourcy.

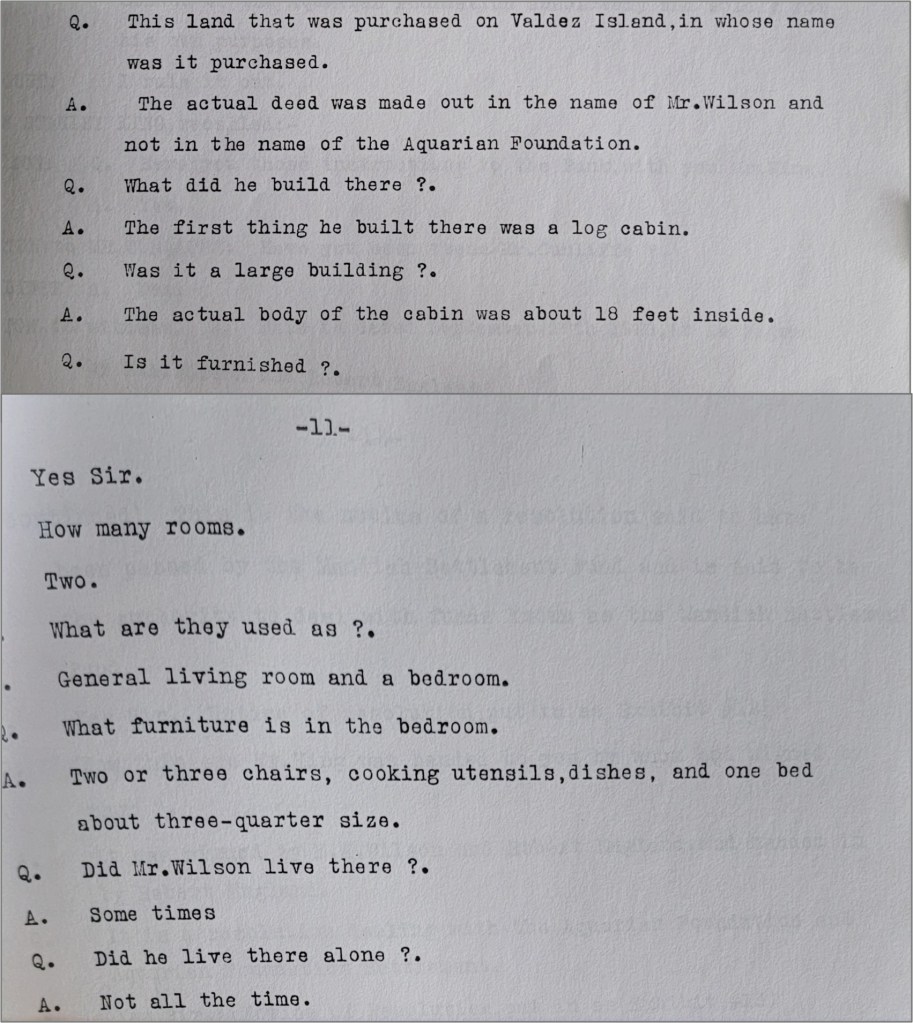

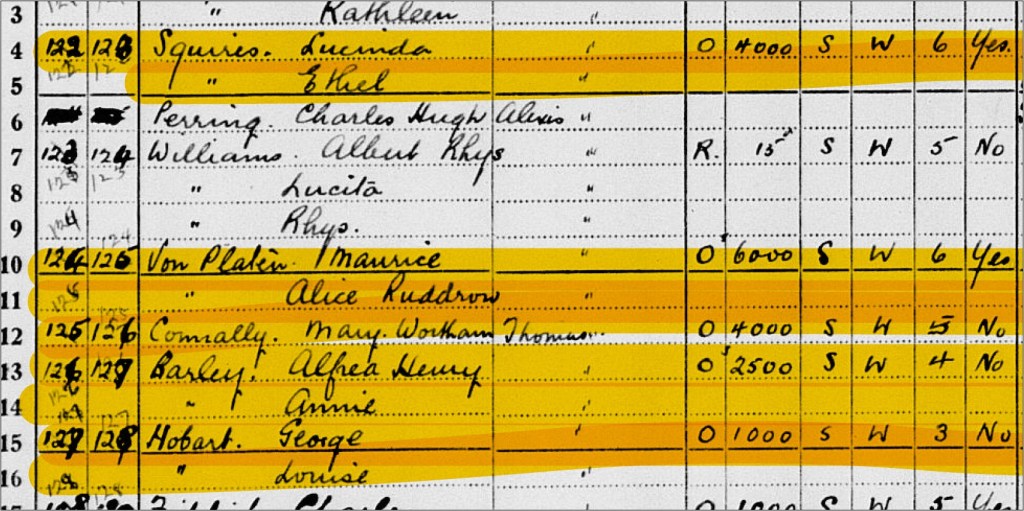

Additional archival materials such as historic newspapers written during the Aquarian Foundation’s active period in BC, the 1931 Canadian Census, court documents, and archived interviews with former Foundation members, also serve as important sources of archaeologically relevant information. For example, court documents from 1928 and 1933 describe some structures built on Valdes and the material goods that were within them, including in some cases the location of those material goods within the structure (e.g. a heating stove was located outside of the bedroom). Newspaper articles written by journalists who visited the Foundation’s settlements also describe the types of structures built and their general locations. The 1931 Canadian Census is especially useful, describing who was living at which settlement in 1931, the construction material of their houses, the value of their houses, and the number of rooms they had. When these are paired with the Foundation’s primary ideological archival materials, a much more nuanced picture of their history in BC begins to emerge from the archaeology.

Archival Materials as Symbolic Objects

Another aspect of the Aquarian Foundation’s archival materials that I’ve been thinking about is the physical materiality of the archival materials and their role as symbolic objects. This also fits in with the objectives of documentary archaeology, as documentary archaeologists see archival materials not only as sources of information, but also as “artefacts that have been produced in particular cultural-historical contexts for specific reasons” (Wilkie 2006:14). Archival materials are pieces of material culture are “contextually significant” and “embedded with social meaning” that can “reflect power as well as resistance” (Broughton Anderson 2014:10114). Archival materials can contain language that can act as “producers of material culture, space, and place” with an ability to modify spaces and behaviours (Broughton Anderson 2014:10114), which can leave archaeological visible impacts to landscapes. Furthermore, some archival materials, such as textual documents, include additional marginalia or notes made on the documents, which moves beyond just the producer of the text to aid in interpreting how an audience may have engaged with the texts. Such notes can provide insight into identity formation and maintenance, evolving thoughts, and the reception of specific narratives (Lubinski 2023:40).

Sociological examinations of the influence of symbolic objects within the context of contentious politics, which includes the study of social movements like the Aquarian Foundation, offer another important lens through which Brother XII and the Foundation’s archival materials can be understood as symbolic objects. Sociologist John Lofland (quoted in Gardner and Abrams 2023a:3) considered symbolic objects to be one of the most basic components of social movements and described them as “all those material items that participants view as physically expressing their enterprise,” which includes “(i) key artifacts, (ii) symbolic places, and (iii) iconic persons.” Key artifacts are the “literal objects that are ‘part’ of it, the material ‘stuff’ of social movements” (Gardner and Abrams 2023a:3) that may or may not be transportable. Symbolic places may include material objects like buildings, and landscapes where “objects may be present by do not wholly form the place in question,” like ancestral trails and historic battlegrounds (Gardner and Abrams 2023a:4). Iconic persons play symbolic roles which may be observable through “theories relating to body politics and body-work,” as well as through the objects that speak of or represent those iconic persons (Gardner and Abrams 2023a:4).

Peter Gardner and Benjamin Abrams emphasized that symbolic objects are “not simply objects, or only symbols: they are at once physical objects and symbolically potent” (Gardner and Abrams 2023b:14). In other words, it is the combination of symbolism and materiality that makes an object a symbolic object. They are dynamic objects with the power to enact and influence individual and collective action through their “capacity to play roles beyond the aims or intentions of the individuals who produce them, bring them, or perform with them” (Gardner and Abrams 2023b:16). Symbolic objects can be transformed both symbolically and materially through acts as small and simple as adding highlights, inscriptions, or signatures on an object, for example, renewing or transforming the object’s power (Abrams and Gardner 2023:301). The power of a symbolic object comes from the “interplay between its symbolic importance and material capacity, mediated by its social context” (Abrams and Gardner 2023:296).

Furthermore, drawing from anthropologist Alfred Gell, Julius M. Rogenhofer and Filipe C. Da Silva distinguished between primary (human), and secondary (object) agency and proposed that symbolic objects “acquire agency from the human actions that form them, essentially rendering material agency as a form of human agency transferred into objects” (Rogenhofer and Da Silva 2024:10). In other words, symbolic objects act as secondary agents “through which humans’ primary agency is distributed to render it effective” (Rogenhofer and Da Silva 2024:10). As objects become “invested with the intentionality of their creators, users, and modifiers,” (Rogenhofer and Da Silva 2024:10) symbolic objects can be seen as significant stimulants of emotional responses to actions and events beyond just their symbolic form. Material culture’s “ability to make abstract ideas tangible” means that the materiality of such objects also plays “an important role in both the physical enabling and ideational narration of events” (Rogenhofer and Da Silva 2024:10).

Brother XII described several of his books, letters, and magazines as outward expressions of the Work that he and the Foundation were instructed to complete by the spiritual Masters of the Wisdom, which were meant to inspire action within his readers. For example, The Chalice magazine was described as a means through which news of the upcoming “New Day” and messages from the Masters would be shared with readers to not only prepare them for spiritual transformations, but also to encourage them to take action against the secret cabal. Brother XII also provided a small list of books that he expected members to have copies of for study, two of which were his own books The Three Truths and Foundation Letters and Teachings. Aquarian Foundation members who participated in external chapters worldwide did so through monthly letters sent to them from Brother XII that contained monthly teaching instructions for reading specific passages from specific books on his small list, as well as instructions for how to physically organize monthly meetings. In summary, it was important for Foundation members to have their own physical copies of the Foundation’s archival materials, to have something tangible to help them feel connected them to the vision. These books, letters, and magazines were symbolic extensions of Brother XII, while at the same time were also material items that acted as physical representations of abstract spiritual and conspiratorial ideas. Beyond just sources of ideological information, these archival materials are also symbolic material objects of the Aquarian Foundation. These are material goods, or artifacts, whose power came through both their symbolism and materiality and which inspired and influenced many additional aspects of the Foundation’s landscapes that are archaeologically observable beyond the physical archival materials themselves, from the types of structures built to the amount, or lack thereof, of personal and household goods used.

In conclusion, archival materials in archaeological research can hold multiple seats of importance. On one hand, they are important sources of insight into the ideologies and worldviews of the people who lived at the sites we examine. They are like a flashlight, shining down to illuminate the archaeology before us. And on the other hand, as I’ve just discussed with regards to Brother XII and the Aquarian Foundation, archival materials can also be important material goods in their own right, with the power to inspire and influence actions and thoughts from the people who engaged with those materials in their lives.

References Cited:

Broughton Anderson, C. 2014. Space, Place, and Architecture in Historical Archaeology. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by Claire Smith, pp. 10112–10119. 1st ed. Springer International Publishing, Cham.

Gardner, Peter, and Benjamin Abrams. 2023a. Introducing Symbolic Objects in Contentious Politics. In Symbolic Objects in Contentious Politics, edited by Benjamin Abrams and Peter Robert Gardner, pp. 1–12. 1st ed. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Gardner, Peter, and Benjamin Abrams. 2023b. Contentious Politics and Symbolic Objects. In Symbolic Objects in Contentious Politics, edited by Benjamin Abrams and Peter Gardner, pp. 13–36. 1st ed. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Lubinski, Christina. 2023. Rhetorical History: Giving Meaning to the Past in Past and Present. In Handbook of Historical Methods for Management, edited by Stephanie Decker, William M. Foster, and Elena Giovannoni, pp. 35–45. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rogenhofer, Julius M, and Filipe C Da Silva. 2024. Politics with Objects? On the Affective Materiality of Contentious Politics. Acta Sociologica 67(1):6–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/00016993231186507.

Skowronek, Russell K. 2014. Archival Research and Historical Archaeology. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by Claire Smith, pp. 492–495. Springer New York, New York, NY.

Van Garderen, Peter. 2007. Archival Materials: A Practical Definition. Peter Van Garderen. https://vangarderen.net/posts/archival-materials-a-practical-definition.html.

Wilkie, Laurie A. 2006. Documentary Archaeology. In The Cambridge Companion to Historical Archaeology, edited by Dan Hicks and Mary C. Beaudry, pp. 13–33. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press.